Print on Parts of Dress to Leave White Areas

Dress shoes, structurally, may be the most complex thing you wear every day. In this article, we'll break down the component parts of a pair of shoes so you can shoe shop like an expert.

Table of Contents

- The Anatomy of a Dress Shoe

Recently on The Gentleman's Gazette, we've discussed the stylistic features that make up a suit and a pair of pants. Continuing further from head to toe, we end up with shoes. When we buy them, we usually choose them first for the style and fit, but rarely for their individual construction.

It's worth a look at the individual parts of a dress shoe so you can be a smart shopper.

The Anatomy of a Dress Shoe

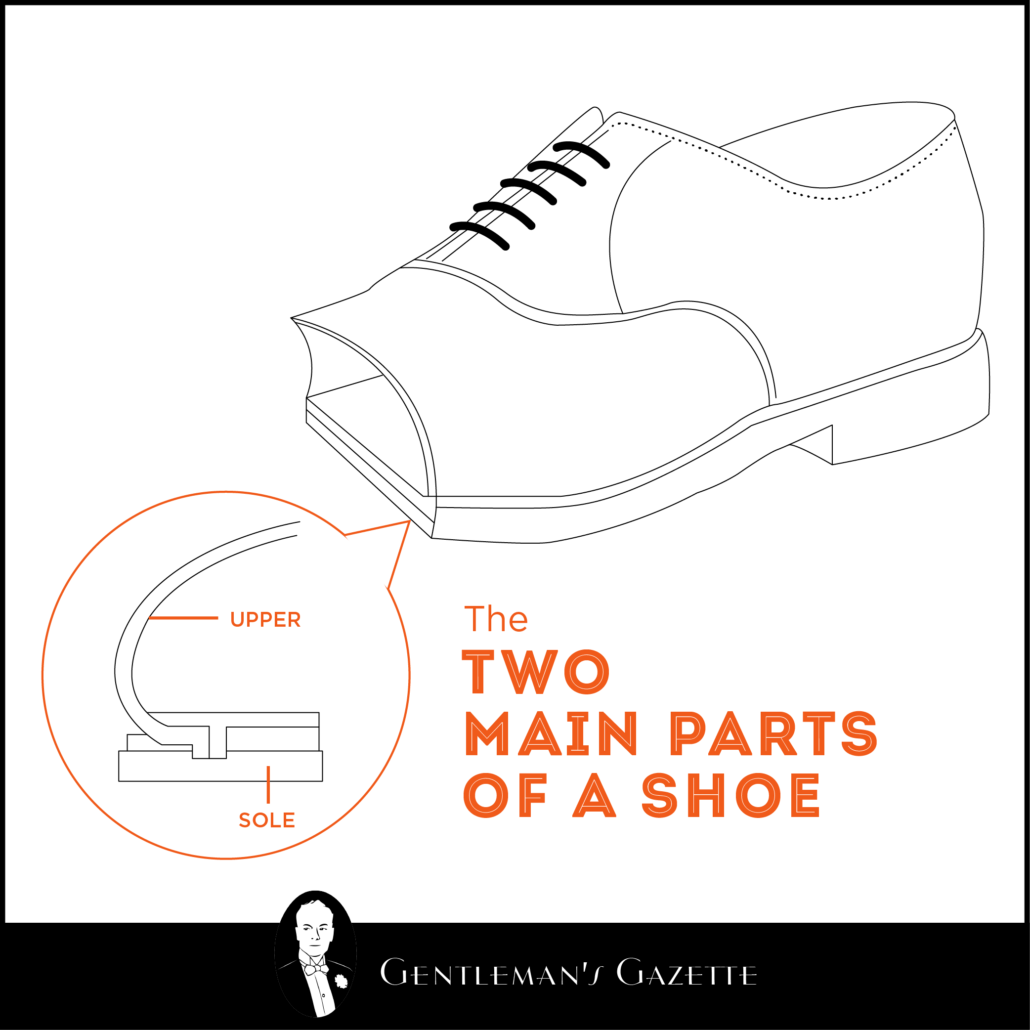

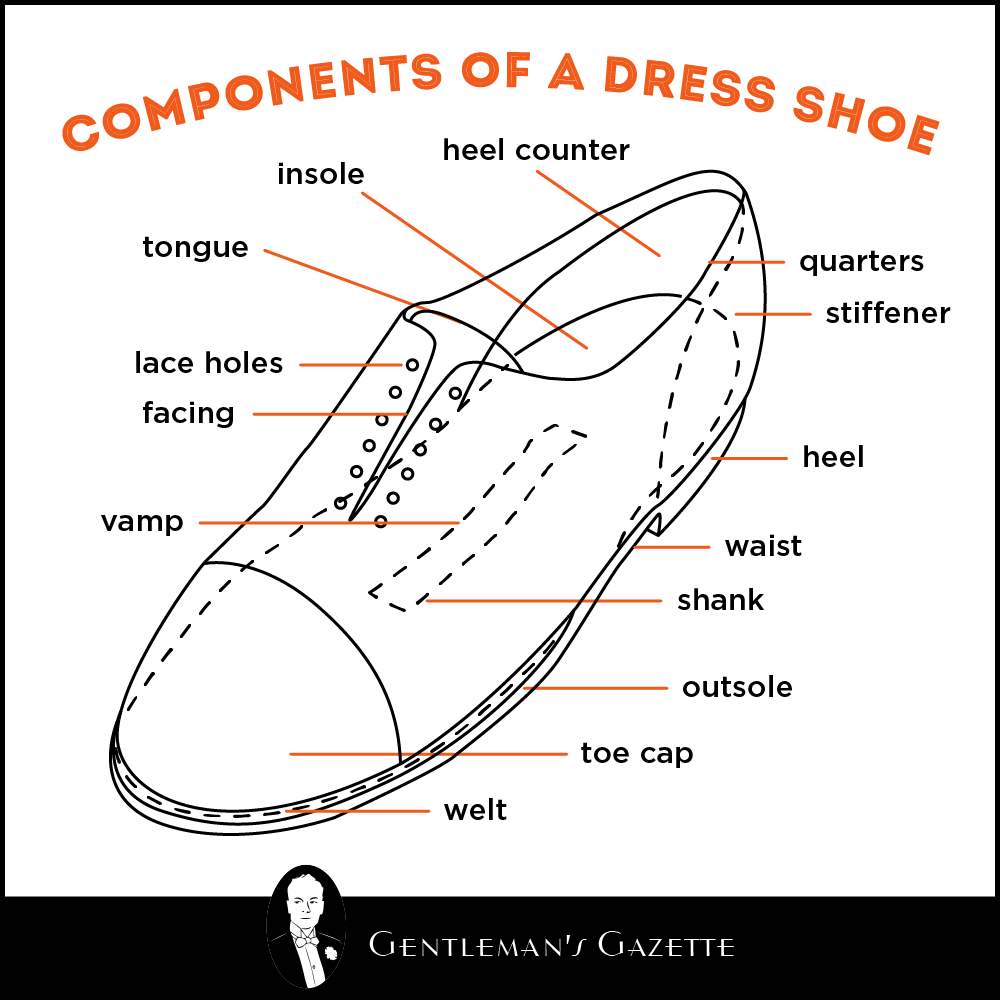

In the broadest sense, a shoe is divided into two main parts, the upper, which is everything on top of your foot plus the lining, and the sole, which makes up the underside. Let's start by taking a look at the upper, the more visible part of the shoe, moving from front to back.

The Toe

The upper is made by stretching leather over a last, a carved form usually made of wood, and leaving it there for some time so that it molds to its shape.

It is eventually secured to the sole with either glue or nails. At the very front of the upper, we have the toe, which can either be simple or embellished, perhaps with a medallion.

This is a pattern made up of perforations in the leather, which makes it somewhat more casual, an unadorned toe being more formal than one with ornamentation. Toe shape on a shoe can vary, and whether it is rounded, almond shaped, or chiseled, plays an important role in the appearance and visual impression of the shoe as well as how comfortably it fits.

The Vamp

Directly behind the toe is the vamp. This is the area that flexes when you walk and is thus subject to creasing. You never want to apply polish, especially wax polish, to the vamp, as it will dry there and crack when the shoe creases, creating a cloudy and caked appearance.

Though some creasing of the vamp is inevitable simply by virtue of the way your foot flexes, it can be minimized by buying shoes made of quality leather and then by storing them with shoe trees to keep the vamp stretched out.

The Quarters

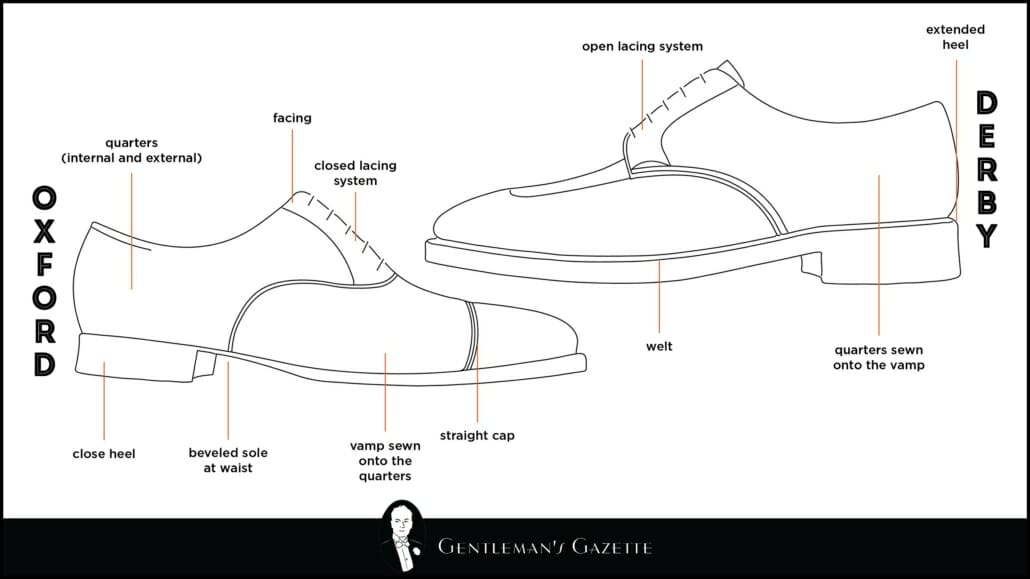

After this come the quarters. The quarters include everything on the upper, including where the laces are up to where the leather wraps around the back of the heel; in essence, the quarters are the sides and back of the shoe. The nature of the quarters is what determines the difference between a derby and an oxford lace-up shoe.

On the former, the quarters are stitched over the vamp, creating two flaps that are then tied together with laces; on the latter, you have the opposite, with the vamp stitched over the quarters. This makes for a cleaner, and therefore more formal, look since there aren't any top flaps of leather. When tying a derby, there will always be some gapping between the flaps, which is referred to as an open lacing system.

On the other hand, the gap on an oxford is minimal, which is why it is referred to as having a closed lacing system.

The laces themselves are threaded through eyelets, usually five pairs, sometimes four, which are punched through the area known as the facing of the shoe. Beneath the facing, you'll find the tongue, a piece of leather that looks like its anatomical namesake. We don't usually think of the tongue of having a specific purpose–it's just "there"–but it's actually designed to protect the top of your foot from the pressure of the laces.

At the back of the shoe is the topline, which is the top edge of the hole into which you put your foot. At the heel, the topline is supported internally by additional leather reinforcement known as the heel counter.

Protecting the heel counter is the reason why you should always use a shoehorn when putting on and taking off dress shoes: jamming your heel against the topline as you force your foot down into the shoe will cause the leather there to buckle and collapse. This can leave permanent wrinkles or deform the area, ruining the fit.

The Insole

Inside the shoe you have the insole, which in a dress shoe should be made of soft leather. The insole provides comfortable, smooth padding for your foot to rest upon.

This footbed contrasts the hard outsole–the lowest part of the shoe–which touches the ground. Between the insole and outsole is the midsole, which can be made up of cork, for cushioning.

Also under the instep of your foot, manufacturers may place a shank–a thin rectangular strip of metal, wood, or fiberglass–that helps to support the foot. The choice of shank material, and whether to use one at all, depends on the brand. For instance, according to a Reddit survey, Crockett & Jones uses wood, Meermin uses steel, and Allen Edmonds doesn't use anything at all.

The Welt

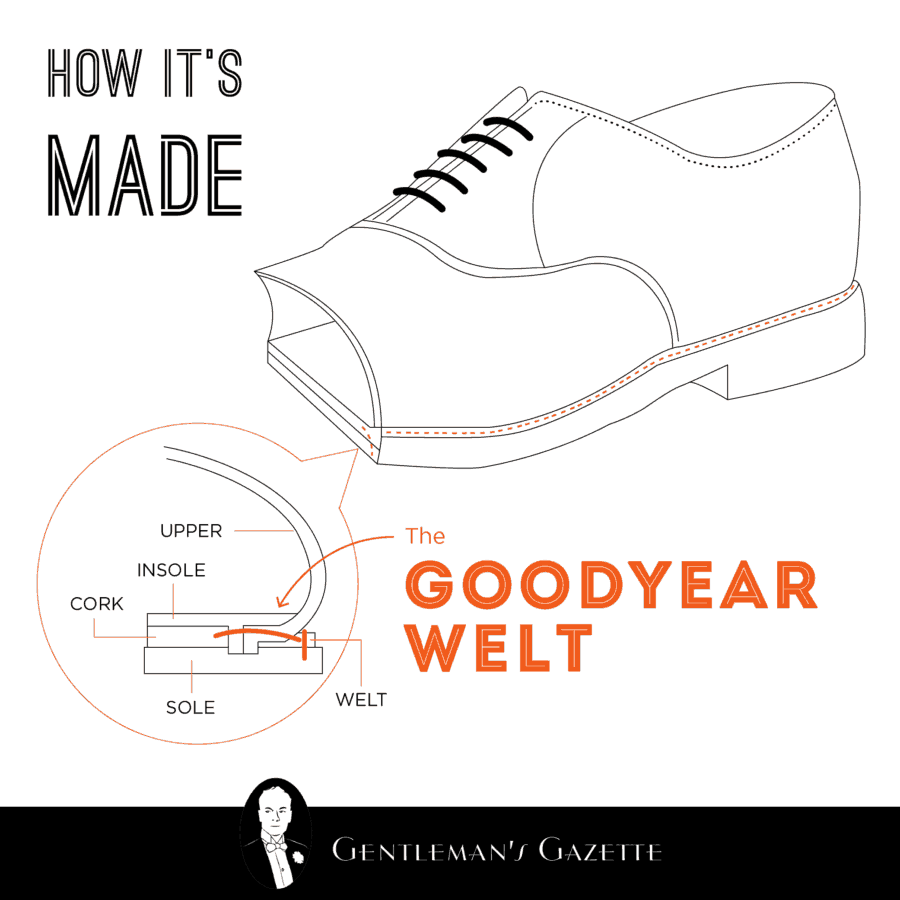

Forming the transition between the upper and the outsole is the welt. This is a thin strip of leather that protrudes around the edge of the outsole to which the upper is secured.

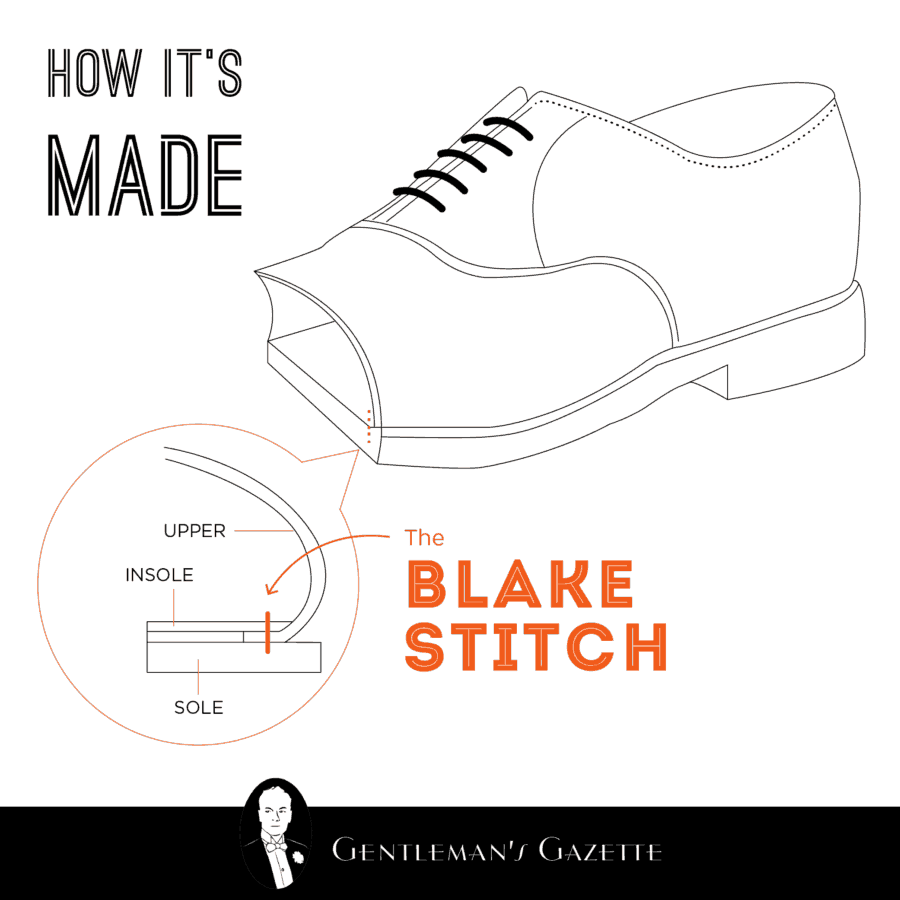

Connoisseurs of footwear will know that the two ways to do this are with a Goodyear welt or Blake stitching. Goodyear welted shoes, named for a machine originally manufactured by Goodyear, are more expensive because of the way the outsole is attached to the upper, which involves a more complex double-stitch approach. Because of this, they can be resoled fairly easily by a cobbler.

The Blake method, on the other hand, involves a simpler stitching method where the insole, upper and outsole are joined together with a single stitch that, while simple to create is difficult to repair.

Because it is made completely inside the structure of the shoe with a machine, resoling the shoe is difficult if your cobbler doesn't possess said machine. And, even then, it is a more laborious and potentially more costly process. For this reason, and because the complexity of Goodyear welting is also matched with other higher quality features, a Goodyear welted shoe is usually worth the investment.

The Sole

The outsole is the lowermost part of the shoe and has to satisfy the double demands of supporting the full weight of the wearer and standing up to the friction of walking on the ground. In a dress shoe, the outsole is commonly made of leather, which is the most elegant, but Dainite (rubber) is also a popular option for those who want more grip and greater water resistance. The thickness of the leather can vary, with multiple layers of outsole appearing in chunkier country derby shoes like those made by Tricker's or Church's in the UK. These may be referred to as "double leather" soles.

With an outsole made of leather there are more opportunities for various structural details that add to its elegance and craftsmanship. One example is a beveled or fiddleback waist.

This used to be seen only on bespoke shoes, but newer technologies have made it accessible in ready-to-wear models. The waist is the narrowest part of the sole, located between the heel and the ball of the foot, directly below the arch of your foot, just as the waist is the narrowest part of the torso in an ideal physique. Beveling the waist shaves down the leather there and gives it a sharp chiseled appearance. The fiddlehead waist occurs when a beveled waist is extended into a V shape toward the direction of the toe.

Finally, we have the heel at the bottom rear of the shoe. Like the outsole, the heel can be built up with individual layers of leather or rubber, and sometimes a combination of both. Rubber is usually reserved for the back edge of the heel, as shown in the Gaziano & Girling image above to provide a measure of grip.

A high-quality dress shoe will usually join the rubber to the leather with a dovetailed joint. An additional touch that you may find on the heel is known as the gentleman's notch or gentleman's corner.

This is a notch sliced from the inside front corner of the heel that was originally designed to keep the wearer's trouser hem from catching on the heel in the course of raising and lowering his legs while walking. This would really only happen with very wide legged pant more common during the Golden Age of menswear, so it's really a vestige of the past than something with an actual purpose now; however, it's a nod to tradition and a sign of an attention to detail.

Conclusion

Shoes are described as being constructed, and true to that term, they are really built of many component parts that come together to make a coherent whole. Usually, we choose shoes based on how they look and how they fit, which are important considerations, rather than for the individual structural features. However, developing an eye for everything that goes into a shoe helps you assess the quality and workmanship.

Source: https://www.gentlemansgazette.com/anatomy-of-a-dress-shoe/

0 Response to "Print on Parts of Dress to Leave White Areas"

Post a Comment